Robot revolution

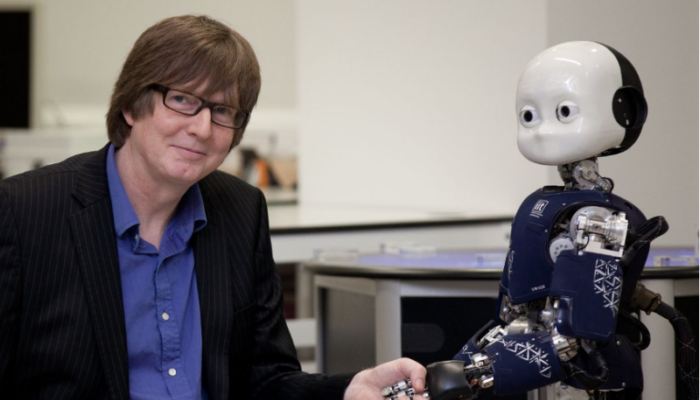

William Walter, managing director of Bridgehead Communications, talks with Tony Prescott, professor of cognitive robotics at the University of Sheffield and director of Sheffield Robotics, to discuss the role of robotics in social care and how further developments can affect the sector in the future

Elon Musk’s recently unveiled the Optimus robot – with the billionaire tycoon making the bold claim that within 20 years there will be more humanoid robots than people. So what should robotics in social care primarily be about and what function should they serve for carers and those in need of care?

“The goal is to help people live in their own homes for longer because that benefits everybody,” Prescott says.

Central to this use of robotics is the continued growth of smart homes. The market for smart appliances for use in the home is expected to grow by more than 10% a year until 2028. This is where he sees the greatest application for this technology in a care setting.

“It might be the case that more and more aspects of the home become automated,” Prescott adds, “rather than thinking of having mobile robots that are looking after you, it might be that aspects of the bathroom are automated in the way that they already are in places like Japan.”

But building on the smart home boom is easier said than done. “The challenge is retrofitting existing homes”, he notes, stressing that “it’s much easier to build these kinds of smart home systems into new accommodation.” Given that the UK’s housing stock is the oldest in Europe, with more than 40% built before 1946, the scope of that technology is limited by Britain’s existing housing system.

Balancing technology with human care

A central question regarding the role of robotics in care concerns the potential dangers of overreliance on machines and the risk of removing the essential human element on which the sector is dependent.

“There are two things involved here. One is physical support, and the other is social support – physical support is less controversial, but it’s also the hardest thing to do,” Prescott explains. “Most existing robots are made of hard parts and could potentially do quite a lot of harm if they’re not controlled very carefully.”

A further possible complication for robotics is a privacy concern, which Prescott notes contributes to the cybersecurity issues regarding these devices, stressing that “these systems need to be less hackable than they currently are.”

However, “the personal data involved”, he adds, “is no different from the cybersecurity issues around other devices that have cameras in the home, like phones and so on.” What he regards as a greater question in care is the difficulty of programming answers to ethical questions.

“There are risks of coercion [for example] if somebody’s not taking their medicine, how much of a role the robot should have.” This is something mitigated in care by the essential part that human decision-making plays.

“Carers deal with these [ethical] issues all the time, of course, and again, we underestimate how important human intelligence is in making those sorts of calls.”

Aiding workforce troubles

The issue most often on display in the ongoing crisis in social care is the shortage of carers. With a vacancy rate of more than 8% and 131,000 posts left unfilled in 2023/24, there are hopes that automation and artificial intelligence could help reduce workforce pressures.

Prescott sees robotics helping with two of the biggest challenges in care: “the working conditions and the pay”. He mentions that “physical injury is a huge problem”, particularly back issues, in delivering care. “So, technology that can help with lifting and moving could [assist] there.”

Referring to the problem of low pay for the exhausting work involved in care, Prescott believes that “one way to make it better paid is to make it more professional by bringing in some of these tools that could be part of the social care support package.”

As such, he adds, “those training to be a social care worker would understand how to use these assistive systems effectively”.

Role of policymakers and government

As we near the end of our discussion, we turn to the importance of state support in driving these developments and innovation. Prescott considers existing support minimal. “If you think about the budget spent on research in this area, it’s pretty thin – a very small amount.”

This, to him, makes little sense because “if you look at the cost of caring for people in residential care and in hospital, it’s a big multiplier compared to the cost of keeping them in their own homes”. So, if you can keep people in their own homes for longer “they’ll be happier about it and it will cost less. It’s a win-win”.

The importance of more significant support in this area is not just more cost-effective than providing hospital or residential care, it can also prove to be a driver of economic activity. “The UK could take a lead here. Currently, Japan and the US are leading in this. One of our issues is we don’t have UK robot manufacturers, but we could have if this is something we could invest in more.

“If you were to spend a fraction of one per cent of the social care budget on research, there would be rewards you could get back in reducing social care costs, which could be quite significant.”

However, the state’s role extends beyond financial support and encompasses regulation too. On this, Prescott has already outlined his support for a “right to human care” in a 2017 White Paper that included a road map for the sector’s future.

“The road map was quite ambitious, but we’re still in the first phase of that,” he comments, but adds that the importance of a legislated right to human care was essential to building support for wider use of robotics in social care. “One of the concerns about robotics is that it would leave people with less access to human carers, and that’s one area where introducing legislation related to a right to human care can reassure people.”

Reflecting on our discussion, Prescott’s vision for robotics in social care presents a nuanced path forward that balances the potential of automation with the essential role of human care. What remains to be seen is how well policymakers can address this sector’s needs to deliver the robotics support that carers and those needing care are desperate for.